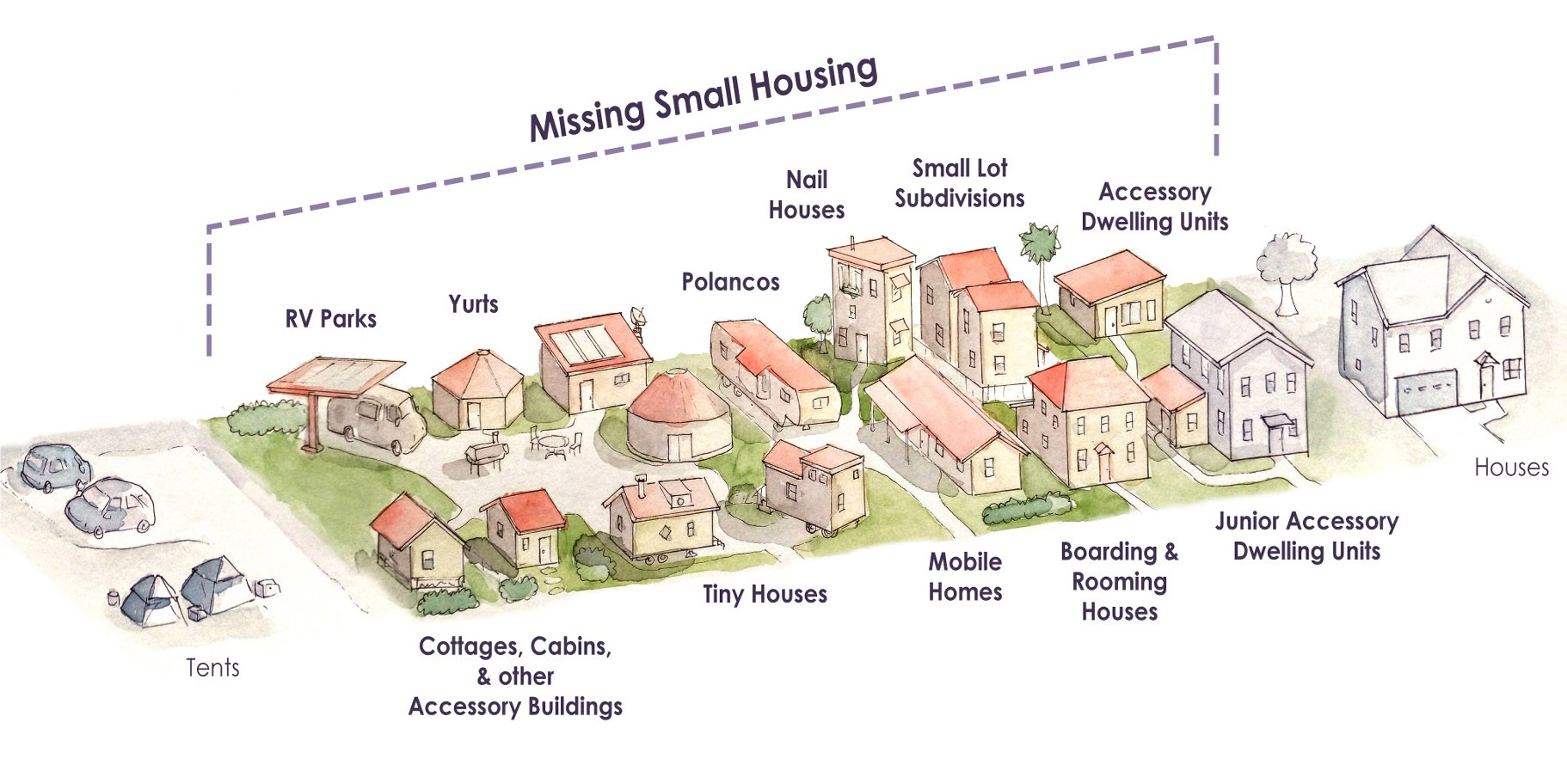

Tiny Town 1. Transitional housing for the homeless.

30 low-cost units, 1 common building shown on a 100 x120 ft lot.

Better than a tent

The homeless live in tents and in doorways because there is nothing better available. Shelters are worse or unavailable. Apartments are unavailable or unaffordable. Governments need to provide something better than a tent – warm and dry, safe and secure accommodation about the size of a tent.

Time for a quick fix

Rather than trying to endlessly solve the “housing crisis”, how about a quick fix? Yes, we need to stop the demolition of older, less desirable but more affordable residential buildings. Yes, we need to build more permanent public housing, and reduce real estate speculation. Yes, we need more public ownership of urban land. And yes, we need to make rental construction more attractive to developers. But all of this will take a lot of time and money. Should municipalities continue to flounder over trying to providing permanent housing for everyone while tent cities become larger, more deadly, more damaging to local business, more demanding of fire, police and health services? Or should they just do what is doable now and provide something better than a tent?

Tiny houses first

We recommend municipalities construct tiny house villages as a quick and inexpensively way to house people living in tents. Tiny house villages (or tiny towns) have been recommended by over 400 community groups in the United States. Warm and dry, safe and secure tiny houses can be built for 1/20 of the cost of a modular housing unit, in 1/10 of the time. A moveable, insulated 100 square foot tiny house, with kitchenette, heating and 12v power can be built for as little as $12,000.

A Better Tent City, Waterloo, Ontario

Tiny but liveable

Tiny houses are small, but address all of the shortcomings of tents. For a single person we recommend 100 ft.² units having a sleeping loft, living area and kitchenette, with shared showers and toilets in a common house. University students live in similar small units with shared showers and bathrooms; so do people who vacation in provincial parks.

Most families in the world live in housing that is under 200 ft.² – about the size of a single car garage.

The missing medium term

Those who need emergency housing can turn to shelters. But there is nothing to accommodate healthy people who need housing for the medium term – 1 to 5 years. Experience shows that tiny house residents eventually move out because they want more space and their own bathroom. Residents stay 6 months on average in Seattle’s 10 tiny towns. The outflow means that others can move in, enabling municipalities to handle the steady stream of people who need a place to live. None of this inflow is created by tiny houses themselves. They do not exacerbate the problem they are trying to solve by attracting homelessness people from other places.

Self-managed = better managed

Andrew Heben, who has created tiny house villages in Oregon, says they should be self-managed rather than run by a non-profit. Residents should set village rules, and allocate routine chores such as cleaning. Villages should also have an operating agreement with the city. A non-profit can play a mediating role, ensuring that a village lives up to its agreement, at the same time advocating for residents at city hall. Non-profits can also find volunteers willing to help with the operation of the village, preparing food, and checking to see everyone is okay.

Andrew Heben is the author of Tent City Urbanism, From Self-Organized Camps to Tiny House Villages.

A huge improvement for 40-50% of the homeless

When someone living in a tent receives a tiny house instead of an eviction notice they are overjoyed. But tiny houses only work for half of those who are homeless. They do not work for those who are severely addicted, or severely mentally or physically handicapped. BC Housing continues to build supportive housing for this group of people, that includes meals, 24-7 staffing and a variety of on-site services.

Finding a site

The lack of a site is the reason usually given for driving the homeless onto public space and then from one location to another. City politicians find it easier to say there is nothing available than endure the complaints of residents who live next to a potential site. But most cities do own land that could be used for village sites, some it remanent land next to roads, bridges and rapid transit. Developers also have land sitting empty waiting for redevelopment, which could be become sites for moveable tiny house villages, with tax incentives from the city.

Speed, costs and regulations

If tiny houses are treated like regular housing, regulations will slow down their arrival and drive up costs. Because of bureaucratic barriers A Better Tent City, a model tiny town in Waterloo, Ontario, had to proceed without asking permission. Tiny houses need to be treated differently, with their construction approved through simple performance requirements rather than complicated prescriptions intended for much larger buildings. Cities also need to modify zoning where necessary to permit tiny-house villages. Currently, most cities ignore buildings under 100 square feet. Costs can be kept under control by building to RV standards, providing 12v power from solar panels, delivering heat from propane tanks, and building ground level floors with treated 2x6s resting on concrete pavers. Large savings can come from reducing the cost of labor. Habitat for Humanity and similar non-profits can dramatically reduce the cost of building a tiny house by using volunteer builders – mostly retirees with tools who want to help.

Some guidelines for building a tiny house village

1 Provide a large common house containing showers and toilets, a community kitchen, and a communal dining and living area. The poor need one another more than those who are better off. A common house is always included in much-lauded co-housing projects. For the poor it is even more important.

2 Build compact row or stacked housing. A village with 30 stacked units, a common building and open space will fit on a 50 x 120 lot. Too many tiny house villages in the US are sprawled over too much space.

3 Aim for attractive buildings with pitched roofs that read as cottages. Avoid ugly steel boxes that look like jail cells or cheap garden sheds.

4 Surround the site with a perimeter chain-link fence with 24-hour security provided by residents.

5 Include landscaped outdoor space.

6 Locate the village near transit and grocery stores, in neighbourhoods that residents regard as their own.

* Note on time and cost

Here is an example. In 2017, The City of Vancouver closed the dilapidated Regent and Balmoral SRO Hotels displacing 300 residents. Six years later the City decided to demolish the hotels after considering renovations; As of May 2023 the hotels remain standing and empty. New replacement units may arrive in another two to three years, costing between $200,000 and $300,000.

* Note on percent

The percentage of the homeless who are healthy varies. Many surveys include cigarettes as an addiction – and acknowledge it is the most common addiction. But cigarette smoking would not preclude someone from living in a tiny town. Only those unable to manage their own lives, or likely to threaten others would be ineligible.

* Note on causes

Most people become homeless as a result of eviction. According to a UBC study, BC has the highest eviction rate in Canada, double the national average. One in ten rental households was evicted in the five years prior to 2021. The authors point out that 85% of these evictions were “no-fault”. In other words, they had nothing to do with tenant behavior but were the result of renovations, demolitions, and other market considerations.

* Note on self-management

Successful villages are self-managed by residents who elect a council from their numbers. The council works with all those in the village to establish rules and penalties, assign chores, and levy fees to cover basic costs. Many villages have a probation period to make sure a new resident will fit in. Rules usually include no alcohol, no drugs, no firearms, no open fires, no violence or stealing, and no abusive language. Failure to follow the rules usually results in a warning. A second infraction can mean temporary or permanent expulsion from the camp. The rules may seem heavy-handed, but they are necessary for a population of many difficult people.

Village Manual and New Member Agreement

Tiny Town 1: single storey

Site: 100’ x 120’ corner lot, 3 – 33′ wide lots, or old gas station site

- level surface with road base, chain-link fenced, landscaped

- buildings: 30 dwelling units, 1 common building.

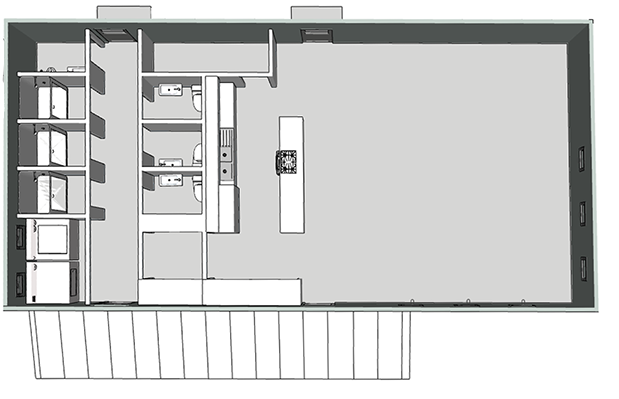

Common building: 24 x 48, 1150 ft.²

- 2×4 wood frame, panelized in 8’ modules for easy disassembly and transport

- foundation: 2’ x 2’ concrete pavers

- community kitchen: 8’ x 18’, dining and recreation open area: 24’ x 24’

- laundry, pantry, closet storage, 12 overhead lockers

- three showers and four sinks draining into a leaching pit

- four toilets using draining into a 16-inch high holding tank, or city sewer

- temporary power pole for the electric stove and electric heat

- estimated cost (Vancouver, 2020): $325,000

Dwelling/sleeping units: 30 – 8 x 12 , 112 ft.²

- 2×4 wood frame, whole unit can be moved or removed from the site

- foundation: 2’ x 2’ concrete pavers

- main floor interior space 84 ft.², loft floor 28 ft.² accessible by ships ladder

- kitchenette: gas cooktop, sink, cold water, grey water drains to a leaching pit, possible under-counter fridge.

- water: city water via protected shallow-buried pex from common building,

- electrical: 12v via protected shallow-buried cable from the common building

- lighting: LED lights

- heating: portable propane heater, two independent safety devices

- windows: 2 clerestory casements, 1 large fixed twin-wall polycarbonate

- lockable back alley for bikes and garbage

- cost per unit $10,000-$15,000 (Vancouver, 2020); 30 units $300,000-$450,000

A note about codes

It should be clear from the outline cost estimate above that the tinytown does not follow conventional building codes. The assumption is that if municipalities really wish to address substandard tent encampments, they will relax prescriptive building codes in favour of performance requirements that serve the same purpose.

Actual costs

Costs are difficult to determine without a site and what the project should include. Construction costs are the sum of many decisions about what will be included. The projected cost for the common building is based on local square-foot construction costs for a wood-frame building of its size. The projected cost of each dwelling unit is based on the cost of similar-sized dwelling units – without donated labour, and but with 20% of materials contributed by local suppliers. There is no sum included for the lease of the land. This proposal assumes that the City will provide a temporary site, the cost of securing the site with a chain-link fence, and site preparation that includes levelling, road base and landscaping

Common building

Tiny Town 2: two storey stacked

Site: 50’ x 120’ lot shown for scale. A larger site such as a double lot, a street end or a remnant site would provide more open space.

- the site could also be a location waiting for development.

- level surface with road base, chain-link fenced, landscaped

- 32 dwelling units, 1 common building.

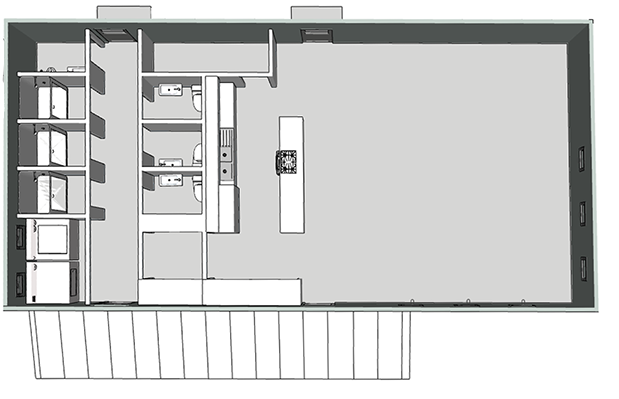

Common building : 24 x 46, 1104 ft.²

- 2×4 wood frame, panelized in 8’ modules for easy disassembly and transport

- foundation: 2’ x 2’ concrete pavers

- community kitchen: 8’ x 18’, dining and recreation open area: 24’ x 24’

- laundry, pantry, closet storage, 12 overhead lockers

- three showers and four sinks draining into a leaching pit

- four toilets using draining into a 16-inch high holding tank, or city sewer

- temporary power pole for the electric stove and electric heat

- estimated cost (Vancouver, 2020): $325,000

Dwelling/sleeping units: 32 – 8 x 12 , 112 ft.²

- 2×4 wood frame, the whole unit can be moved or removed from the site

- foundation: 2’ x 2’ concrete pavers

- main floor interior space 84 ft.², upper units have 28 ft.² loft accessible by ships ladder

- kitchenette: gas cooktop, sink, cold water, grey water drains to a leaching pit, possible under-counter fridge.

- water: city water via protected shallow-buried pex from common building,

- electrical: 12v via protected shallow-buried cable from the common building

- lighting: LED lights

- heating: portable propane heater, two independent safety devices

- windows: 2 clerestory casements for upper units; 1 large fixed twin-wall polycarbonate, plus 1 entry window, and 1 louvred vent for lower units

- lockable back alley for bikes and garbage

- cost per unit $10000-$15,000 (Vancouver, 2020); 32 units $320,000-$480,000

Upper storey

Lower storey

Common house

More Information

A Better Tent City video – How volunteers make it happen

Tiny Homes – a great publication from BC Housing

CBC National story on A Better Tent City

Some cities have succeeded in reducing homelessness

Singapore’s approach to housing

Finland: Homelessness is not an option

The Non-capitalist Solution to the Housing Crisis